|

Source

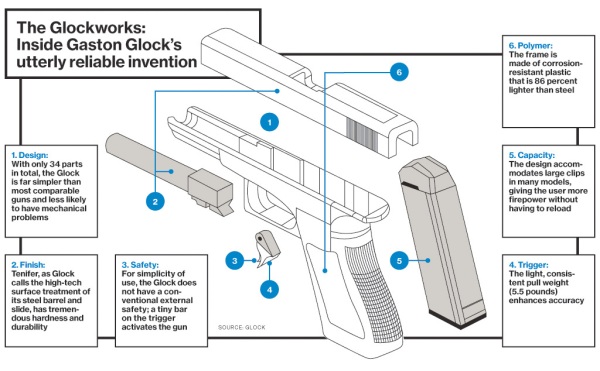

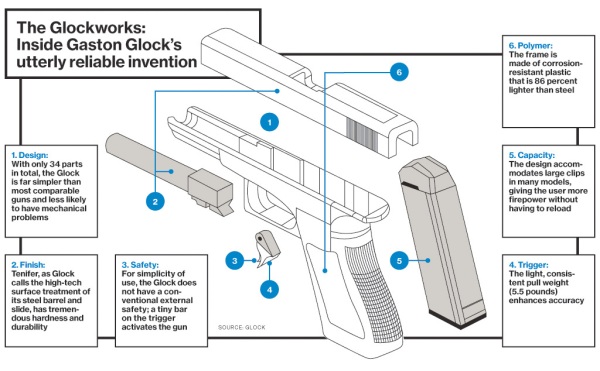

Glock: America's Gun How Austria's Glock became the weapon of choice for U.S. cops, Second Amendment enthusiasts, and mass killers like the alleged Tucson gunman Jared Loughner RICK GERSHON/GETTY IMAGES By Paul M. Barrett January 17, 2011 The Killing Machine For all the anguish and outcry in the days after a community college dropout named Jared Loughner allegedly sprayed a Tucson crowd with 33 bullets from a semiautomatic pistol, one response was notably absent: any sense that America's latest shooting spree, which killed six people and wounded 14, including Representative Gabrielle Giffords, would bring new restrictions on the right to own or carry large-capacity, rapid-fire weapons. The gun control debate has vanished from American politics, but it wasn't always so invisible. Twenty years ago, when another apparently deranged man fired a semiautomatic pistol into a crowd, killing 23 people in Killeen, Tex., politicians rushed the microphones to denounce the weapon itself as "a death machine," as Representative John Conyers Jr., a Michigan Democrat, put it on the floor of the House. A so-called assault weapons ban became law three years later. That law has now expired. Since Loughner's attack, liberal pundits, gun control advocates, and congressional backbenchers have been talking about instituting new controls. The voices that count, however, including President Barack Obama and the congressional leaders in both parties, have had nothing to say on the subject. Their silence is just one measure of how thoroughly Gaston Glock—a former curtain-rod maker from Austria whose company manufactured the pistols used in Tucson and Killeen—has managed to dominate not just the American handgun market, but America's gun consciousness. Before Glock arrived on the scene in the mid-1980s, the U.S. was a revolver culture, a place where most handguns fired five or six shots at a measured pace, then needed to be reloaded one bullet at a time. With its large ammunition capacity, quick reloading, light trigger pull, and utter reliability, the Glock was hugely innovative—and an instant hit with police and civilians alike. Headquartered in Deutsch-Wagram, Austria, the company says it now commands 65 percent of the American law enforcement market, including the FBI and Drug Enforcement Administration. It also controls a healthy share of the overall $1 billion U.S. handgun market, according to analysis of production and excise tax data. (Precise figures aren't available because Glock and several large rivals, including Beretta and Sig Sauer, are privately held.) With all those customers and that visibility, it's no surprise that the Glock has also been the gun of choice for some prolific psychopaths. Byran Uyesugi used a Glock 17 to kill seven people at a Xerox (XRX) office in Honolulu in 1999. Seung-Hui Cho, who murdered 32 at Virginia Tech in 2007 before killing himself, used the same Glock 19 model that Loughner is accused of firing in Tucson. Steven Kazmierczak packed a Glock 17 when he shot 21 people, killing five, at Northern Illinois University in 2008. The smooth-firing Glock did not cause these massacres any more than it holds up convenience stores. But when outfitted with an extra-large magazine, it can raise the body count. The shooters in Arizona, Illinois, Virginia, Hawaii, and Texas could not have inflicted so many casualties so quickly had they been armed with old-fashioned revolvers. In its 2010 catalog, the manufacturer boasts that while the Glock 19 is "comparable in size and weight to the small .38 revolvers it has replaced," the pistol "is significantly more powerful with greater firepower and is much easier to shoot fast and true." The Tucson gunman demonstrated those qualities all too vividly. Loughner is said to have emptied his 33-round clip in a minute or two, a feat requiring no special skill. (Glock does not sell magazines of that size to civilians, but some of its guns can accommodate them. The model 19 comes with a standard 15-round clip.) Loughner was wrestled to the ground by onlookers only when he paused to insert a fresh magazine. If he had been forced to reload sooner, the odds are good there would be fewer victims. Glock executives did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Loughner seems to have had no trouble acquiring his Glock and its oversized magazines, and, for an array of reasons, it's unlikely the harrowing crime will lead to any new curbs on Glock's efficient brand of firepower. For that the company can thank a remarkable chain of unintended consequences—including gun control opponents who fueled public interest in Glock and gun control laws that boosted sales. The more gun foes tried to ban or curb Glock's weapons because of their potency, the more the company turned those attacks to its advantage. Even the tragedy in Tucson has been a boon. Bloomberg News reported on Jan. 11 that $499 Glocks were selling briskly in Arizona. "We're doing double our normal volume," said Greg Wolff, owner of a pair of stores in Phoenix and Mesa called Glockmeister. The Engineer For decades until the early 1980s, Gaston Glock ran a radiator plant in suburban Vienna. On the side, he manufactured window fittings and bayonets in his garage, using a secondhand Russian metal press. Now 81 and living reclusively at a lakeside resort in southern Austria, Glock got his start in guns by listening closely to the customer. In 1980 the Austrian army was looking for a new sidearm to replace the antiquated Walther P-38. Steyr, Austria's premier arms maker since the mid-1880s, offered a clunky update that tended to misfire. Glock, though he had no firearm expertise, saw an opportunity. He studied the best pistols available and consulted with leading European firearm experts. "We sit together and made the plan and drawing," he recalled in a March 1998 legal deposition in the U.S. "It was like a pistol in the future." The army colonel in charge of procurement wanted a pistol that was light, durable, and capable of holding more than the eight rounds the Walther accommodated. Glock solved the puzzle with plastic. He fabricated a frame from an injection-molded polymer, a featherweight material that proved remarkably strong and corrosion-resistant. In the evenings he tested crude early versions in a basement firing range. He shot alone, using only his left hand, so that if the gun blew up he would still have his right to do mechanical drawings. In 1981, Glock filed for an Austrian patent—his 17th, so he called the gun the Glock 17. Coincidentally, it could store 17 rounds in its clip, with an 18th in the chamber. In competitive trials for accuracy and durability in 1982, the Glock defeated models made by Steyr and four other well-known European arms manufacturers. The Austrian military ordered 20,000, and Gaston Glock had cracked the gun business. When Karl Walter, a firearm salesman based in the U.S., first picked up a Glock during a visit to a Vienna gun shop in the spring of 1984, his reaction was, "Jeez, that's ugly." The squared-off pistol lacked the blued-steel frame and polished wooden grips of a classic American revolver. Its black matte finish seemed homely. "But still, I was extremely curious why the Austrian army bought it," Walter says. "There had to be more to it than what meets the eye initially." A native Austrian, Walter sold imported rifles to American police departments, traveling from town to town in a motor home custom-fitted as a rolling gun showroom. For years he had nurtured an idea about handguns: "Where there really is money to be made is to convert U.S. police departments from revolvers to pistols." Ever since the 19th century, when the Colt Peacemaker became known as "the gun that won the West," Americans had preferred revolvers. Continental Europeans favored pistols, also known as semiautomatics, with spring-loaded magazines that snap into the handle, holding more rounds and allowing faster reloading. "I was astonished," Walter says, "that this modern country still hung around with revolvers." In 1984 he paid a call on Gaston Glock and offered to sell his pistol in America. They made a complementary pair: Glock, the reticent engineer, unfamiliar with the U.S. and its taste in guns, had a breakthrough product. Walter, the garrulous expat, had valuable connections in the world's richest gun market. In 1985, Walter set up Glock's American subsidiary in a small warehouse-and-office complex near the Atlanta airport in Smyrna, Ga. He launched at the perfect time. A year later, America's police collectively decided they needed a new handgun. Police Pistol With violent, cocaine-driven crime on the rise—the U.S. gun homicide rate increased 39 percent between 1983 and 1993—police saw themselves as outgunned. There was little statistical support for this; the typical police gunfight at the time involved the firing of two to three rounds by the cops—well within the capacity of a Smith & Wesson (SWHC) revolver. The number of officers killed in the line of duty had peaked in 1974 at 279 and declined to 178 in 1986. But in several notorious incidents, including a shoot-out in Miami in April 1986 that left two FBI agents dead, the bad guys deployed more firepower than the law enforcers. "Although the revolver served the FBI well for several decades, it became quite evident that major changes were critical to the well-being of our agents and American citizens," FBI Director William S. Sessions said after the Miami bloodshed. Walter garaged his RV and began zooming around in a Porsche, pitching the Glock to force after force. In late 1986 the Miami Police Dept. ordered 1,100 pistols, followed closely by Dallas, San Francisco, and others. "It's the wave of the future," said the chief in Minneapolis, who authorized Glocks for his officers. In December 1986, Curtiss Spanos, a cop in Howard County, Md., fired 16 rounds in a 30-minute pursuit of two armed robbery suspects. The Glock saved his life and his partner's, he told The Washington Post. "There would be two dead officers if I didn't have the 9 millimeter gun." At that time, gun control advocates trying to thwart the Austrian invader made their first strategic misstep. They claimed that because it was mostly plastic, the pistol would be invisible to X-ray machines. "Only the barrel, slide, and one spring are metal," the late Jack Anderson wrote in his syndicated column in January 1986. "Dismantled, it is frighteningly easy to smuggle past airport security." Antigun groups mobilized, Congress held hearings, and the National Rifle Assn. rallied its troops. "The amazing thing was that nobody had ever heard of Glock before the Anderson column," says Richard Feldman, a lawyer then working for the NRA. " 'Glock? What's that? Oh, an Austrian gun, a plastic gun? Interesting. I've got to see one of those.' " As the 17-round pistol became an object of curiosity and admiration among Second Amendment enthusiasts, the anti-Glock campaign fizzled. The Federal Aviation administration concluded that if screening personnel paid attention, they would be able to detect the pistol. "That was a big 'oops' moment," says Richard M. Aborn, a former president of Handgun Control Inc., now known as the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence. "We made the classic mistake of failing to do our homework." Hollywood, never known for accuracy, gave Glock another boost. In Die Hard 2: Die Harder, released on July 4, 1990, mercenary terrorists swarmed the big screen armed with Austrian pistols. The hero, played by Bruce Willis (who carried a Beretta), at one point yelled at an airport police captain: "That punk pulled a Glock 7 on me! You know what that is? It's a porcelain gun made in Germany. It doesn't show up on your airport X-ray machines, and it costs more than you make here in a month." It didn't matter that everything Willis' character said was inaccurate, says Feldman, the industry operative who later did consulting work for Glock. "You had Jack Anderson, and Congress, and now Bruce Willis—everyone's making things up about Glock. And gun owners, they want to defend the 'porcelain gun' or the 'plastic gun' or the 'hijacker special,' or whatever the media are calling it. What fabulous publicity." Ban Backfires In September 1994, after a string of grisly shootings—the 1989 Stockton (Calif.) elementary school attack, the 1991 Killeen massacre, the 1993 Waco siege—Congress passed the assault weapons ban, which President Bill Clinton immediately signed. The law, which limited magazine capacity to 10 rounds, seemed likely to hurt Glock. It had the opposite effect. Long before the law's enactment, Glock was running its factory at full tilt. "We're getting 5,000 guns and 8,000 to 9,000 magazines a week from Austria," Dick Wiggins, a Glock representative, told the Minneapolis Star Tribune in May 1994. "We're tens of thousands of orders behind," he added. "Our pistols are scarcer than hen's teeth." As a compromise to get the law passed, the Clinton Administration had agreed to allow continued sale of gear manufactured before the ban. Glock executives figured the new law would incite a buying frenzy, and they were right. "People who own guns that use magazines holding more than 10 rounds—including the Glock 9mm popular with police—are buying extra magazines as fast as they can," USA Today reported. " 'We were cleaned out of magazines in the space of a few hours,' says Mike Saporito of RSR Wholesale Guns of Winter Park, Fla., which supplies thousands of retail shops. 'Sales have gone through the roof.' " Seventeen-round Glock clips that had sold for less than $20 quintupled in price over the next few years. The unintended consequence of the law was that more high-capacity weapons and magazines ended up in stores, at gun shows, and on the street. Indeed, "the Clinton gun ban," as the NRA called the legislation, created a fascination with large clips that hadn't existed before in civilian gun circles. The Austrian company found new ways to feed the demand the law had unintentionally created. Having supplied scores of major police departments with 9mm weapons in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Glock gave these agencies the opportunity to trade in their modestly used pistols for brand-new ones. The exchanges earned the company powerful customer loyalty and gave Glock another large batch of pre-ban magazines that could be resold on the burgeoning used market. In one exchange in late 1994, Glock received 16,000 used high-capacity clips and more than 5,000 older pistols from the Metropolitan Police Dept. of Washington, D.C. Asked whether Glock was circumventing the magazine law, its in-house counsel, Paul F. Jannuzzo, sounded indignant. "It's not a way around the crime bill. It is well within the law," he told The Hartford Courant. "I'm not sure what the spirit of the crime bill was. I think the whole thing was an absolute piece of nonsense." Glock also responded to the assault weapons ban by designing and marketing a new generation of smaller handguns whose clips held 10 or fewer rounds—"Pocket Rockets," as Glock called them. In 1995 the company introduced the Glock 26 and Glock 27 in 9mm and .40 caliber, respectively. (The Glock model-number system tells one nothing about the nature of the weapons.) The barrel and grip of the new models were an inch shorter than standard Glocks, but the ammunition packed just as much punch. The guns could be conveniently tucked into a pocket or purse: "a perfect choice for women," Glock said in a press release. At the same time, the NRA—a powerful and, for the industry, inexpensive lobbying arm that is funded mostly by gun-owner members—was stepping up a nationwide campaign in support of state laws that gave civilians the right to carry concealed handguns to shopping malls, Little League games, and almost anywhere else. Pocket Rockets were ideal for suburban concealed carry. Before 1987 only 10 states had right-to-carry laws. In 1994 and 1995 alone, 11 states enacted such statutes, bringing the total to 28. "The gun industry should send me a basket of fruit," Tanya Metaksa, the NRA's chief lobbyist at the time, told The Wall Street Journal. "Our efforts have created a new market." Today, 48 states allow concealed carry; only 10 of those require applicants to provide a reason. Arizona, Alaska, and Vermont do not demand any kind of permit at all. As Glock grew, reaching sales in the U.S. of roughly $100 million by the late 1990s, according to two former company executives, the company had to withstand new courtroom assaults from municipalities allied with plaintiffs' lawyers who sued gunmakers the way states had gone after tobacco companies. Jannuzzo, the company's corporate counsel, gained influence, eventually taking the lead executive role in the U.S. once held by Walter, who had left over a compensation dispute. More Permissiveness A former prosecutor in New Jersey, Jannuzzo displayed a boxer's talent for jabbing and feinting while opponents tired themselves out. In 2000 he sent signals publicly and privately that Glock might agree to settle the municipal litigation then being orchestrated by the Clinton Administration. In exchange for protection from future liability, Glock and other corporate defendants would acquiesce to unprecedented marketing restrictions. At the 11th hour, however, Jannuzzo rejected the deal, leaving Glock rival Smith & Wesson as the only industry participant. A retail boycott encouraged by the NRA nearly drove S&W out of business, while Glock reveled in a temporary sales surge. The entire settlement collapsed in 2000 and became moot when a GOP-controlled Congress passed a statute in 2005 to protect gunmakers from such suits. Glock had played a risky game and won again. Lost in the process was a rare opportunity for an industry that makes inherently dangerous products to police their promotion and sale more vigorously. The gun control movement was flagging long before 2005. In the closely contested Presidential election of 2000, Al Gore had lost his home state of Tennessee in part because of NRA opposition, and Democrats decided that gun control was a cursed issue. President George W. Bush made noises about extending the assault weapons ban and magazine limit, but when the NRA and Republicans on Capitol Hill resisted, he allowed the law to expire in September 2004. Glock led the charge back into the large-capacity clip business. Other gun and accessory makers also pushed ever-larger magazines. Today, Sportsman's Warehouse in Tucson, where Loughner bought his Glock, advertises a 50-round "Tactical Solutions Drum Magazine" for .22 caliber Ruger rifles priced at $64.99. The store also sells Glock-factory magazines, designed for six to 17 rounds, at $29.99 apiece. The outlet's website notes, however, that "compact and subcompact Glock pistol model magazines can be loaded with a convincing number of rounds—i.e. … up to 33 rounds." The online store CDNN Sports, based in Abilene, Tex., advertises 33- and 31-round Glock-compatible mags that it labels "Asian Military MFG." Only six states—California, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York—now have their own limits on large magazines. High-efficiency weapons make American criminals deadlier, and in extreme cases, such as Tucson, large magazines make them deadlier still. Compared with other industrialized Western democracies, the U.S. does not have an especially high level of crime, or even violent crime. What it does have is "a startlingly high level—about five times the Western European/Canadian/Australian average—of homicide," UCLA public policy professor Mark A.R. Kleiman writes in his 2009 book, When Brute Force Fails. The U.S. "also has an astoundingly high level of private gun—especially handgun—ownership," an estimated 100 million civilian handguns. Gun homicide rates are higher in the U.S., Kleiman argues, because robberies, residential burglaries, and aggravated assaults committed with guns are all more lethal. Why, then, is all the movement on gun regulation toward more permissiveness? One key reason is that after rising from roughly 1963 through 1993, crime began to drop off. In 1993 there were 9.5 murders and non-negligent manslaughters per 100,000 inhabitants, according to the FBI's annual Crime in the United States. By 2009 that rate had fallen 47 percent, to 5 per 100,000. Offenses committed with firearms also fell sharply. The reasons are a matter of dispute. Possible factors include a sharp rise in the rate of incarceration, improved policing methods, and the burning-out of rivalries among crack gangs. Gun control advocates credit point-of-purchase background checks and the assault weapons bill. More rigorous studies indicate that those laws actually had negligible effects on crime, according to Kleiman. Polls show that even most people who support stricter gun control do not believe that such laws reduce crime generally. "At some basic level," Dennis Henigan, vice-president of the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence, acknowledges in his 2009 book, Lethal Logic, "the public is convinced that 'when guns are outlawed, only outlaws will have guns.' This belief cannot help but diminish the intensity of public support for further gun restrictions." The rise of the Glock and other semiautomatic handguns cannot be linked to variations in overall crime rates. But that doesn't mean it would be pointless to take small steps to reduce mayhem, such as restricting magazine capacity. One lesson of Tucson is that there is a difference between a 33-round clip and an 8- or 10-round clip. The only way to make a limit work, though, would be to ban the manufacture, sale, and possession of all clips larger than the cap. Reviving a porous 1990s-style limit would backfire. Representative Carolyn McCarthy (D-N.Y.), among others, is working on a new restriction. "We are optimistic it will plug the loopholes in the 1994 law," says Kristen Rand, legislative director of the Violence Policy Center, a gun control group that is consulting on the bill. Even if quite modest, however, the provision seems unlikely to receive serious consideration in a Republican-controlled House of Representatives. Glock's victory, and that of its industry, won't be reversed anytime soon. With Michael Riley. This article draws on Bloomberg Businessweek Assistant Managing Editor Paul M. Barrett's reporting for a forthcoming book on Glock and its influence in America, to be published by Crown in 2012.

Glock's High-Capacity Bullet Magazines By Paul M. Barrett BW Magazine For fans of the Glock semi-automatic pistol, one perk available at company-sponsored shooting competitions is the opportunity to buy extra-large 33-round magazines manufactured at the Glock factory. "We all probably own one or two just for the heck of it," says Steve Denney, a former police officer who manages the Pro Arms gun store in Live Oak, Fla. "I hate to use the word after Tucson, but for most of us, it's just a novelty." Glock factory-made 33-round magazines are also available from major gun-and-ammo distributors such as Midway USA, based in Columbia, Mo. On its website, Midway advertises the extra-large black polymer bullet container as "a factory original magazine for your Glock." The $35.99 item is currently out of stock and on backorder, the site indicates. Glock does not ship the extra-large magazines with the guns it sells to civilian gun owners, leading to some ambiguity about whether the company itself makes the 33-round components for consumers. Denney and other people in the industry clarified that the Austrian-based company does make the extended magazines. "We have some Glock ones here in the store," he says. Glock executives and a company spokeswoman didn't respond to phone and e-mail requests for comment. A 33-Round Magazine Emptied in Tucson The shooting spree Jan. 8 in Tucson that left six dead and 14 wounded, including Rep. Gabrielle Giffords (D-Ariz.), focused renewed attention on so-called high-capacity handguns. Investigators say the Tucson gunman used a 33-round magazine in a Glock 19 nine-millimeter pistol to spray more than 30 bullets in just a minute or two. Larger magazines allow a shooter to fire more rounds before having to reload. The manufacture and sale of new magazines containing more than 10 rounds were banned from 1994 through 2004, at which time the federal prohibition expired. In response to Tucson, Democrats in Congress are circulating draft legislation to reinstitute curbs on large ammunition magazines. Bill de Blasio, the elected public advocate in New York, suggested in a written statement on Jan. 13 that if Glock continues to market 33-round magazines, the city's police department should boycott the company's firearms. New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg said on WOR radio that "we need a law to stop you from selling" extended magazines, but rejected the notion of a boycott. Bloomberg explained that the NYPD buys handguns from three manufacturers—Glock, Smith & Wesson, and Sig Sauer, all of which make the extra-large magazines. "If we boycott one, you probably have to boycott all of them, and then you go back to the days when the crooks had better guns than the cops," Bloomberg said. (The mayor is founder and majority owner of Bloomberg Businessweek parent Bloomberg LP.) Extended Magazines: Cumbersome Thirty-three round magazines are not of much practical use to law-abiding gun owners, according to Denney, the Florida firearm retailer. That's because the extended magazines stick out awkwardly from the base of a pistol's handle, making it impossible to carry in a conventional holster. "I guess people get them if they want to expend a whole bunch of ammo at the range, maybe for a YouTube video or something," Denney says. "I don't know what else you would do with it." A variety of gun-accessory makers now sell 33-round magazines compatible with semi-automatic pistols manufactured by Glock and other firearm companies. Glock, which is based in Deutsch-Wagram, Austria, typically sells its pistols with more modest magazines, containing 8, 10, 15, or 17 rounds, according to the Glock website. The site notes that six Glock pistols, in a variety of calibers, are compatible with 33-round magazines. "Glock pistols are superior in firepower to conventional pistol models of the same size," the site states. The Glock 19 that was identified as the shooter's weapon in Tucson is sold with 15-round magazines as standard equipment. Wholesale and retail gun distributors sell Glock "factory original" 33-round magazines as separate accessories. At least on some occasions, Glock sells them directly to participants at civilian shooting-range competitions sponsored by its affiliate, the Glock Shooting Sports Foundation. Law enforcement officials have not identified the source of the Tucson gunman's magazines. Jared Loughner, the alleged shooter, is said to have possessed four in total—the one he emptied, an additional extended model, and two that could hold 15 rounds. Barrett is an assistant managing editor at Bloomberg Businessweek. |